FSAs and Regular Expressions

Contents

Introduction

A Finite State Automaton (or just FSA) is a mathematical model of computation. A regular expression (or RegEx for short) is the algebraic representation of an FSA.

In less abstract terms, a regular expression is a description for a pattern of text.

Regular expressions are helpful when it comes to checking for certain patterns. With patterns, you can do many things such as complex replacing (way more powerful than Ctrl+F), extremely simple input validation, finding specific patterns amongst extremely large amounts of data very quickly, and data extraction / parsing. You can also write cool, unintelligible expressions like

^(?:\s*(?:=.*?=|<.*?>|\[.*?]|\(.*?\)|\{.*?})\s*)*

(?:[^\[|\](){}<>=]*\s*\|\s*)?([^\[|\](){}<>=]*)

(?:\s*(?:=.*?=|<.*?>|\[.*?]|\(.*?\)|\{.*?})\s*)*$

that are actually useful.

In ACSL, FSAs will be limited to parsing strings.

Understanding FSAs

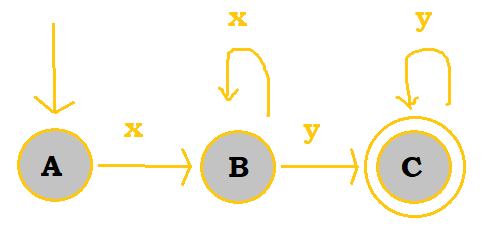

In a FSA, there are states, which are marked as circles. Only one of these states can be active. All that really means is that the state you are currently at is "in use", and thus active.

The initial state has an arrow pointing toward it from nowhere (i.e. this arrow does not come from any other state). The final state is marked as a double circle.

To go from one state to another, we have transition rules, which are shown as labeled edges (the arrows labeled with xs and ys).

Transition rules can also go from one state to itself; however, these rules may occur 0 or more

times.

Here's an example FSA that parses Strings that consist of x's and y's:

Here, we have A, B, and C as our states. A is the initial state whereas C is the final state. There are transition rules that exist between either two different states or a state and itself.

To go from state A to state B, the FSA must "see" the letter x in the input String. Then, when it gets to state B, there are two options. If the FSA sees an x, then B will stay as the active state; if it sees a y, then the FSA will move to C, which becomes the new active state. Any additional y's will keep C as the active state.

Once the string has been completely processed, it will be deemed as accepted by the FSA as long as the FSA is at the final state.

So, the FSA above would accept xy, xxy, xyy, xxxxy, and much more. In general, the FSA above would accept any string that is composed of one or more x's followed by one or more y's.

Regex

You can create a regular expression out of an FSA, and vice versa. When it comes to regex, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- A null string (marked with the lambda sign,

$\lambda$) counts as a string/character (it's just the equivalent of""in regular programming.) - If a and b are both regex, then so are the following:

$ab$- This is just a followed by b; it does not mean and like it would in boolean algebra. The proper term for this would be concatenation.$a\cup b$or$a\,|\,b$- This stands for a or b. The proper term for this is union. (In almost every programming language or sensible implementation of regex, the pipe symbol|is used.)$a*$- This is a repeated 0 or more times. This is known as closure, or the Kleene star (named after Stephen Cole Kleene, the computer scientist who invented regular expressions and helped establish recursion theory).

As always, order of precedence still exists. It goes: Kleene star, concatenation, and then union.

Parentheses still hold the highest priority. For example, /dca*b/ would produce strings like

dcb, dcab, dcaaaab, and so on. On the other hand, /d(ca)*b/ would produce db, dcab,

dcacacab, etc.

Syntax

Specific syntax rules vary depending on the implementation or the programming language/library being used. The syntax rules below are more universal across all regex packages, which is why ACSL chose to cover them.

In regex, a string matches if it can be represented completely by a regex.

ACSL presents these symbols in a long list; however, it is easier to understand if you classify them into different classes.

- Tokens - These are things that literally match a part of the string. For example,

/a/is just a token that represents the charactera. - Quantifiers - These are things that tell you how many times you can repeat the previous token.

- Group Constructs - For now, this is just the parenthesis

/( )/and the OR operator/|/- we'll go into more detail about groups below and why they're useful.

You might've also noticed the syntax highlighting of the regex on this page. Here's how the highlighting is done for each class: (This is in accordance with IntelliJ's Darcula theme.)

- Tokens - Regular, literal string tokens (like just

/a/) are green. However, special tokens (like/./), ranges (e.g/[A-Za-z]/), and other tokens whose meanings aren't just match literally just what this token says, are highlighted in yellow. - Quantifiers - These are highlighted in blue.

- Group Constructs - The OR operator is highlighted in orange

/|/, and any groups are highlighted in yellow.

Also, we'll go over the actual syntax in programming languages further down (this is just ACSL's syntax for programming competitions - however, do note that actual regex has all the below syntax in it too.)

Tokens

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Matches | Doesn't Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/./ |

A wildcard; it can represent any character. | /a.b/ |

acb, a7b, a‽b |

ab, accb |

/[ ]/ |

It matches a single character within the brackets. A range can be specified with a dash. | /[abc]/ or /[a-c]/ |

a, b, c |

abc, d |

/[^ ]/ |

It matches a single character not within the brackets. A range can be specified with a dash. | /[^abc]/ or /[^a-c]/ |

f, h, z, 2 |

a, b, c, fz |

Quantifiers

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Matches | Doesn't Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/*/ |

This matches the preceding token 0 or more times. | /ba*/ |

b, ba, baa, baaaaaa |

bbaa, aaa |

/?/ |

This matches the preceding token 0 or 1 times (basically, makes the previous token optional). | /colou?r/ |

color, colour |

coloer |

/+/ |

This matches the preceding token 1 or more times. Not to be confused with /*/ - this requires at least one of the preceding token. |

/a+h/ |

ah, aaah, aaaaaah |

h, aaahh |

Group Constructs

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Matches | Doesn't Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/|/ or $\cup$ |

Standing for 'or', this separates alternatives. Notably, ACSL prefers the $\cup$ syntax. Also, note that parentheses are not required to group this specific operator - it tells the regular expression to either match everything to the left of it or everything to the right of it. For instance, in the example on the right, the /|/ doesn't just apply to g and c but to dog and cat. To limit its scope, you need to use parentheses to group it. If you want more options, just add more pipe operators ( /a|b|c/ matches a, b, and c). |

/dog|cat/ |

dog, cat |

dogat, docat |

/( )/ |

This is used to define a sub-expression. The contents cannot be separated. As said before, these take the highest priority. | /(ab)+/ |

ab, abab, ababab |

aabb |

Other Syntax Notes

Quantifiers, for obvious reasons, can only follow tokens. You cannot put a quantifier directly behind another quantifier (something like a**)

(well, technically you can - /a*?/ is what's called a lazy quantifier, and

/a*+/ is what's called a possessive quantifier in some flavors of regex. However,

for all ACSL purposes, you can't put a quantifier behind another quantifier.)

Identities

It may take a bit to really understand why these identities are valid, but be sure to take your time. It's always better to reason with the logic behind each identity so that they become common sense rather than something you have to memorize.

Although frankly, for most of these identities, memorizing them won't be much use at all. Just use these to get the hang of how regex works (treat them like practice for understanding regex logic). Don't even bother trying to memorize them.

| Identity | Explanation |

|---|---|

/(a*)*/ = /a*/ |

The /a*/ means "0 or more as", and /(a*)*/ means "0 or more as 0 or more times". So basically, they both just say "print as many as as you want". /a*/ is essentially the simplified version of /(a*)*/. |

/aa*/ = /a*a/ |

Let's say /a*/ displayed 1 a for both the LH and RH expressions in this equation. /a*a/ and /aa*/ would both print aa. So, regardless of which a in the regex receives a /*/, the evaluation is the same (note that these are both also equivalent to /a+/). |

/aa*|λ/ = /a*/ |

/aa*/ would display a 1 or more times. However, since we're saying the the String could also be null (/λ/), then we simplify this to /a*/. (I don't know what ACSL has against /a+/, but they just never use it for some reason, and use /aa*/ instead. Weird.) |

/a(b|c)/ = /ab|ac/ |

/b|c/ means that either b or c will be displayed. a will definitely be displayed; this is because the parentheses make it so that the /|/ only applies to b and c. So, the display may be ab or ac, which we can write down as /ab|ac/. |

/a(ba)*/ = /(ab)*a/ |

Let's say that the characters in the parentheses display twice. /a(ba)*/ would print ababa, as would /(ab)*a/. The same applies if the characters in the parentheses were displayed any other amount of times. (This isn't a very useful property. I'm not sure why ACSL chose to show it.) |

/(a|b)*/ = /(a*|b*)*/ |

/(a|b)*/ would print either a or b (not both, the /|/ is evaluated first because parentheses have priority) zero or more times, which is just /a*/ and /b*/. /(a*|b*)*/ states that either /a*/ or /b*/ (again, not both) will be displayed 0 or more times. We know from a previous identity that /(a*)*/ and /(b*)*/ are just /a*/ and /b*/ respectively, which matches with what /(a|b)*/ displays. |

/(a|b)*/ = /(a*b*)*/ |

Again, /(a|b)*/ displays either /a*/ or /b*/. For /a*/, /(a*b*)*/ could have it so that /b*/ displays b 0 times. The expression would simplify to /(a*)*/, or /(a*)/. A similar idea applies if we wanted /b*/. |

/(a|b)*/ = /a*(ba*)*/ |

/(a|b)*/ displays either /a*/ or /b*/. For /a*/, we could have it so that /(ba*)*/ displays 0 times; we would then be left with /a*/ as we wanted. For /b*/, we could have the two /a*/ in the RH expression display a zero times. The expression would then become /b*/. |

Regex in Programming

Much of this is adapted from Chapter 7 of Automate the Boring Stuff. Read that for an at-length introduction into the world of regular expressions in programming (assuming you're somewhat familiar with Python syntax). I highly recommend reading it if this section either goes too fast for you or you still don't understand the applications of regular expressions.

If you don't want to bother with reading that, however, this section is basically the SparkNotes version.

Let's start with the biggest question: Why do I need to learn regex? - Regex oftentimes seems like a foreign language that you never want to touch or bother with, because you're never going to use them anyway, right?

Wrong. In fact, you couldn't be more wrong. Out of everything I have learned in the last 2 years about computer science, the one thing I used the MOST was regex. It is incredibly useful (not just for programming). Knowing regex can simplify a task from manually editing 500,000 database entries to writing one find-and-replace command.

This quote from Automate the Boring Stuff sums it up pretty well:

"Regular expressions are helpful, but few non-programmers know about them even though most modern text editors and word processors, such as Microsoft Word or OpenOffice, have find and find-and-replace features that can search based on regular expressions. Regular expressions are huge time-savers, not just for software users but also for programmers."

If you still don't have any interest in learning more than is absolutely needed for ACSL about regex, you can skip this section.

Click here to skip to Sample Problems

Regex is very, very useful. Don't believe me?

Example Use

Let's say you have a field in a website. You want to check if what's in that field is a valid phone number - you don't want to call an invalid phone number like "chicken" and have your program crash.

We're just going to do a simplified version of this, with a single string we're checking to see if it's a phone number.

The format is going to be predefined as xxx-xxx-xxxx (something like 123-456-7890).

Without Regex

Let's try writing a solution for this without regex in Java.

First, we know that the phone number is going to be 12 characters long.

We'll check every individual location to see if it's a number or a dash.

public static boolean isPhoneNumber(String str) { //str being our potential phone number

String numbers = "1234567890";

if(str.length() != 12) {

return false; //because a length of anything other than 12 would violate our predefined xxx-xxx-xxxx format

}

if (!str.substring(3, 4).equals("-") || !str.substring(7, 8).equals("-")) {

return false;

}

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++) { //check if any of the chars (indices 0-2) of str are not numbers

if(!numbers.contains(str.substring(i, i + 1))) {

return false;

}

}

for(int i = 4; i < 7; i++) {

if(!numbers.contains(str.substring(i, i + 1))) {

return false;

}

}

for(int i = 8; i < 12; i++) {

if(!numbers.contains(str.substring(i, i + 1))) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

This is very, very painful code, not only to write, but also to debug or expand to other number formats. (Imagine having to do this with (xxx)xxx-xxxx).

It becomes even more painful when you look at the regex solution.

public static boolean isPhoneNumber(String str) {

return str.matches("\\d{3}-\\d{3}-\\d{4}");

}

Yep. One line. It does the exact same thing.

This regex - /\d{3}-\d{3}-\d{4}/ - does EXACTLY the same check in one line (the backslashes are doubled because

you have to escape them in Java, because there are no raw string literals where you don't have to escape backslashes,

because JEP 326 for Java 12 was rejected because the Java developers think somehow

two backslashes for every single regex delimiter and FOUR BACKSLASHES to match a single literal backslash in regex

doesn't cause Leaning Toothpick Syndrome and force you

to destroy your code readability by double escaping everything in regex - this is why I use Python instead

no I'm not salty at all don't @ me. -Raymond)

Now you might be wondering: What's that /\d/ symbol? Why are there curly brackets?

To answer that, we'll need to delve into the actual syntax.

Syntax (Again)

All the syntax ACSL uses is preserved in actual regex, but actual regex has a much richer set of features.

Let's split these symbols again, by their types. I'll be doing a more abbreviated version here with only the most common symbols (that I've found to be more than enough for everyday use) - you can find the full set of regex syntax in various reference sheets online.

Quick reminder of the types:

- Tokens - These are things that literally match a part of the string. For example,

/a/is just a token that represents the charactera. - Quantifiers - These are things that tell you how many times you can repeat the previous token.

- Group Constructs - This includes parenthesis

/()/, capturing groups, non-capturing groups, alternation (/|/), and other constructs that help you manage specific locations in your regex / form some sort of groups. I'll tell you more about capturing groups a bit further down.

And a few more notes:

- Like mentioned above, Java requires double-escapes for every backslash inside a string (so they're not interpreted incorrectly.)

So think of every pair of two backslashes in your Java string as one backslash in your regex string. (Yes, this means matching a literal

backslash in Java regex requires

\\\\since the backslash itself requires the escape sequence\\) - Syntax varies slightly depending on the flavor of regex - the regex expressions that follow will mostly be PERL flavor (this is the one that most programming languages, Java and Python included, use.)

- Anything that isn't listed as special here is a literal token.

- If you want to enter something in regex that's a special character, but you want it to be interpreted as literal, escape it with a

\(i.e./\./matches a literal.)

Tokens

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Matches | Doesn't Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/./ |

A wildcard; it can match one of any character (may or may not match line breaks, depending on regex string settings - usually will not) | /a.b/ |

acb, a7b, a‽b |

ab, accb |

/[ ]/ |

A character class - it matches a single character within the brackets. A range can be specified with a dash. | /[abc]/ or /[a-c]/ |

a, b, c |

abc, d |

/[^ ]/ |

It matches a single character not within the brackets. A range can be specified with a dash. | /[^abc]/ or /[^a-c]/ |

f, h, z, 2 |

a, b, c, fz |

/\d/ |

Matches a single digit from 0 to 9. Equivalent to /[0-9]/. |

/-?\d/ |

-1, 5, 3 |

-25, -a, b |

/\w/ |

Matches a single alphanumeric character ("word" character, hence the w). This means 0-9, a-z, A-Z, and underscores (basically anything you can put in a Minecraft username). Equivalent to /[a-zA-Z0-9_]/. |

/\w{3,16}/ |

Any valid Minecraft username | a a a a a, mince^raft |

/\s/ |

Matches a single whitespace character (tab, space, carriage return, new line, vertical tab, form feed (yes all of these are characters lol)). Especially useful for handling any wacky spacing in input with a /\s*/ |

/Hello\s+there!/ |

Hello there!, Hello(\n)there!, Hello(tab tab tab)there! |

Hellosthere! |

/\D/ |

Matches a single character that DOESN'T match /\d/ (isn't a digit from 0 to 9). (Opposite of /\d/, basically.) |

|||

/\W/ |

Opposite of /\w/. |

|||

/\S/ |

Opposite of /\s/. |

|||

/\b/ |

A word boundary. Matches, without actually taking up any characters in the match, immediately between a character that matches /\w/ and one that doesn't. In the String version, think of it like replacing the /\b/ with any non-alphanumeric character. |

/.*\bis\b.*/ |

that is cool, is that cool |

islands suck, israel isn't istanbul |

/\B/ |

Opposite of /\b/ - matches, without actually taking up any characters in the match, immediately between two characters that match /\w/. In the String version, think of it like replacing the /\b/ with any alphanumeric character. |

/.*\Bis\B.*/ |

bliss |

this, that is cool |

Quantifiers

/+/, /*/, /?/… you know them, you love them. They're included here again for the sake of completeness, along with a few other

quantifiers that ACSL won't tell you about.

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Matches | Doesn't Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/a+/ |

Matches one or more of a. |

/a+h/ |

ah, aaah, aaaaaah |

h, aaahh |

/a*/ |

Matches one or more of a. |

/ba*/ |

b, ba, baa, baaaaaa |

bbaa, aaa |

/a?/ |

Matches zero or one of a (optional). |

/colou?r/ |

color, colour |

coloer |

/a{n}/ |

Matches exactly n of a, with n being a number. |

/\d{4}/ |

1234 |

231, 52355 |

/a{n,}/ |

Matches exactly n or more of a, with n being a number. |

re{2,} |

ree, reeee, reeeeeeeeeee |

re, ee |

/a{n,m}/ |

Matches a between n and m times (inclusive), with n and m both being numbers. |

we{2,4} |

wee, weee, weeee |

we, weeeee |

Now, there are also lazy and possessive quantifiers.

Here's a very brief summary of both:

Lazy Quantifiers

You put a ? behind a quantifier to make it lazy (i.e. a+?)

Lazy quantifiers mean that in ambiguous situations, they will capture the shortest string possible (instead of the longest string possible, as is the default behavior). As this is a summary, I'll just show a brief example.

<p>test</p>

Given this very brief snippet of HTML, this regular expression: /<.*>/ will match the entire thing <p>test</p>, as it is between a < and a >,

while this regular expression /<.*?>/ (using a lazy quantifier) will only match <p>, as it will stop as soon as it possibly can.

This does have its fair share of applications, but that's beyond the scope of this introduction.

Possessive Quantifiers

You put a + behind a quantifier to make it possessive (i.e. a++)

Similar to greedy quantifiers, but even greedier. It refuses to share. This means that once it captures something, it will refuse to give it back.

For example, given the following string:

whyyyyyy

/why+y/ will match. We can take it as the y+ matched with yyyyy, and the extra y after the + matched with a single y. However, /why++y/ will NOT match. The y++ will eat every single y in the expression, and the final y will not get matched,

leading to a complete match failure.

Meaning, whereas with /why+y/ where whyyyyyy was a match due to y+ matching yyyyy, y++ would

take every y it can and thus match with yyyyyy. This leaves the final y with nothing to match with, thus resulting in failure.

This is mostly useful for improving the performance of your regular expression in situations where that matters (so basically, I'm saying that you're probably never going to use this. It's not nearly as useful as lazy quantifiers.)

Group Constructs

Here comes the fun part!

You might be wondering how to use a regular expression to parse input. (Our previous captain, Raymond, believed that nobody would read this far into this resource. In his words, "You're probably not, but whatever. I doubt anyone is reading this far anyway". As per tradition, (9/14/2023), if anyone is reading this, tell HaroldasD on Discord and I'll get the captains to do something for you. -- You forgot to close the parentheses. Also, how did you set the date as 2024 when 2023 isn't even over yet? - Former captain Raymond who still has push access to the repository -- You're so mean to me Raymond D: )

Say hello to the most basic of group constructs: the capturing group.

/()/

Wait, isn't that just parenthesis?

Aha, you feeble-minded ACSL simp who is only here for the college credit. You fool. You moron.

Unbeknownst to both you and ACSL, the parenthesis were serving a sinister function. They were capturing whatever was in them.

This is by far the most useful thing for parsing using regular expressions.

For example, let's say I have a problem. I want to find the area code of someone's phone number.

I simply do this:

/(d{3})-d{3}-d{4}/.

This, unbeknownst to you, populates the first "group" of the regular expression with the first 3 digits.

For example, if I matched this regular expression onto 123-456-7890, we'd have 123 in the 1st group.

The only other construct I'll be going over here is the non-capturing group: /(?:something)/

This is literally treated the same as you would expect regular parenthesis to be. They don't capture anything,

they literally just group. There's a bunch of other constructs that I won't go into at this time.

If you would like to do a deep dive into regular expressions, you will begin finding incredibly alien terms, such as:

- Catastrophic Backtracking

- Negative/Positive Lookaround Assertions

- Backreferences and Relative Backreferences

- Atomic Grouping

- Regular Expression Recursion (note: I still don't understand why this is a thing. It will make your brain hurt.)

- Subroutines

I… well, you can learn about this if you want. Do you have to? No. Frankly, I'm just shocked you read this far.

One last thing before you go: Some example code.

Example Code

Java

//forget the import statements, just auto import, it's somewhere in java.util

public class WhyAmIHere {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile("(\\d{3})-\\d{3}-\\d{4}");

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher("123-456-7890");

// you must call this in order for the regex search to be performed

if(matcher.find()) {

System.out.println(matcher.group(1)); // "123"

}

// simpler regex for when you don't need groups

System.out.println("123-456-7890".matches("asdfgh")); // false

}

}

Python

import re # or something

phone_number = re.compile(r"(\d{3})-\d{3}-\d{4})")

test = phone_number.search("123-456-7890")

print(test.group(1)) # 123

print(test.group()) # 123-456-7890

Like I said before, these use what's called different "flavors" of regular expressions - certain things are different, but all the core functionality is the same. Look up language documentation for more specific details.

Sample Problems

1. Which of the following regexes are equivalent?

/(a|b)(ab*)(b*|a)//(aab*|bab*)a//aab*|bab*|aaba|bab*a//aab*|bab*|aab*a|bab*a//a*|b*/

First off, one choice that we can eliminate immediately is #5 because null strings λ are valid matches;

the other 4 choices don't accept λ as a match.

Also, notice that #2 will always display an a at the end regardless of the OR in the

parentheses. The other 3 choices don't have to display an a at the end (they can, but they don't have to).

So, we can eliminate #2.

We are now down to #1, #3, and #4. Take a look at #3 and #4; they are, for the most part, identical.

However, their third OR alternative differs; #3 has $a\,a\,b\,a$ whereas #4 has

$a\,a\,b*a$. So, #3 and #4 must not be equivalent.

So, the question now is, are #1 and #3 identical? Or is it #1 and #4? What we can do is list out what strings #1 can display.

Here are the possible strings for #1 (we'll use a table to separate each subexpression).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Final Result |

|---|---|---|---|

/(a)/ |

/(ab*)/ |

/(b*)/ |

/aab*/ |

/(a)/ |

/(ab*)/ |

/(a)/ |

/aab*a/ |

/(b)/ |

/(ab*)/ |

/(b*)/ |

/bab*/ |

/(b)/ |

/(ab*)/ |

/(a)/ |

/bab*a/ |

Then, we can see if #3 and #4 can create each of those strings; if it can't create even one of

them, then it must not be identical to #1. #3 would be unable to create $aab*a$ since it only

has $aaba$; so, #1 and #4 must be identical.

2. Which of the following strings would be accepted / matched by the regex below? List all correct answers.

/abb*(a|b*)a(b*|a*)/

ababbaabababaaaabbabbbbababbaababbaa

We can do this by just looking at all 5 of the strings.

Let's look at #1. /abb*(a|b*)a/ can match aba just fine. However,

/(b*|a*)/, which

produces only as or only bs, cannot match bbaab. Hence, #1 doesn't match.

A similar idea applies to #2; /(b*|a*)/ cannot match ba.

As for #3, it doesn't match because the string must start with ab.

For #4, it would match. /abb*(a|b*)a/ can display abbbba. The final b

can be displayed by /(b*|a*)/, so #4 matches.

The last option would not be valid because babbaa cannot be produced by /(b*|a*)/.

So, only #4 would actually be accepted.

Another (probably better) way to do this problem would be to translate the regex into plain English and do it intuitively. This particular regex means:

| Regex | English |

|---|---|

/abb*/ |

Matches ab literally, followed by b 0 or more times |

/(a|b*)/ |

Matches either a literally or b 0 or more times. We can simplify this into just an /a?/ because we know /b*b*/ (if we choose 2nd option) is just /b*/, meaning that this part matcher either a or nothing. |

/a/ |

Matches a literally |

/(b*|a*)/ |

Matches either a 0 or more times or b 0 or more times |

Then we can compare our plain-English description against the different strings, in left-to-right order.

Here is a brief description of how you might do this intuitively:

| String | Explanation |

|---|---|

ababbaab |

ab literally, followed by b 0 times. Although the next character is an a, we will not match with that and will instead match with b 0 times so that we don't fail the next part. Then a literally. Last part can't match remaining bbaab. |

ababa |

ab literally, followed by b 0 times. Although the next character is an a, we will not match with that and will instead match with b 0 times so that we don't fail the next part. Then a literally. Last part can't match remaining ba. |

aaabb |

Can't match ab literally. |

abbbbab |

ab literally, followed by b 3 times. Although the next character is an a, we will not match with that and will instead match with b 0 times so that we don't fail the next part. Then a literally. Last part matches remaining b. |

abbaababbaa |

ab literally, followed by b 1 time. Match with optional a and not b*. Then a literally. Last part can't match remaining babbaa. |

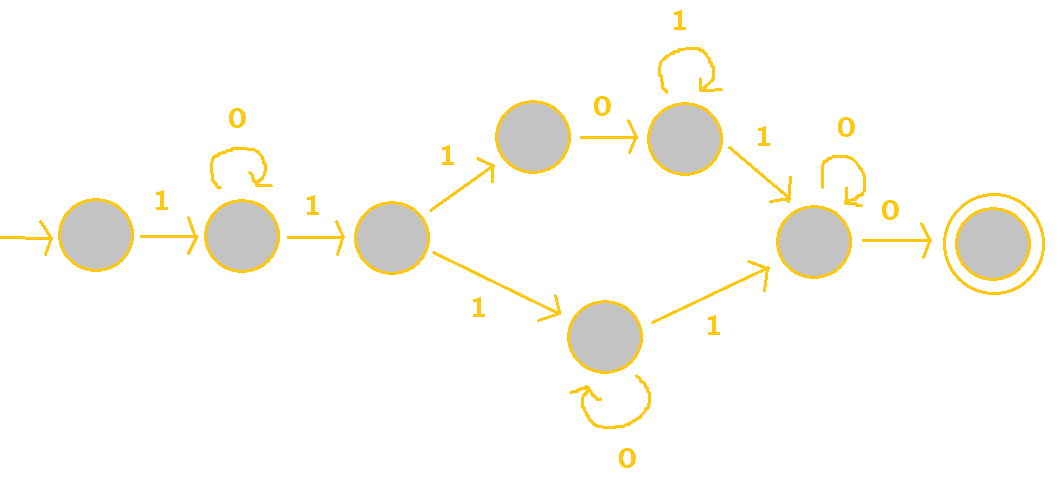

3. Determine what strings would be accepted by the following FSA. Make your answer general. (So basically, give us a regular expression.)

The fork in the FSA represents a union. If we were to take the upper "path", we would have a

string of /10*1101*10*0/. If we took the lower path, we'd have /10*110*10*0/.

Notice where they are the same and where they differ.

They both share /10*11/ at the beginning as well as /10*0/ at the end. The middle conflicting

portion can be written as a union in our final regex.

So, we would have /10*11(01*|0*)10*0/ as our regex.

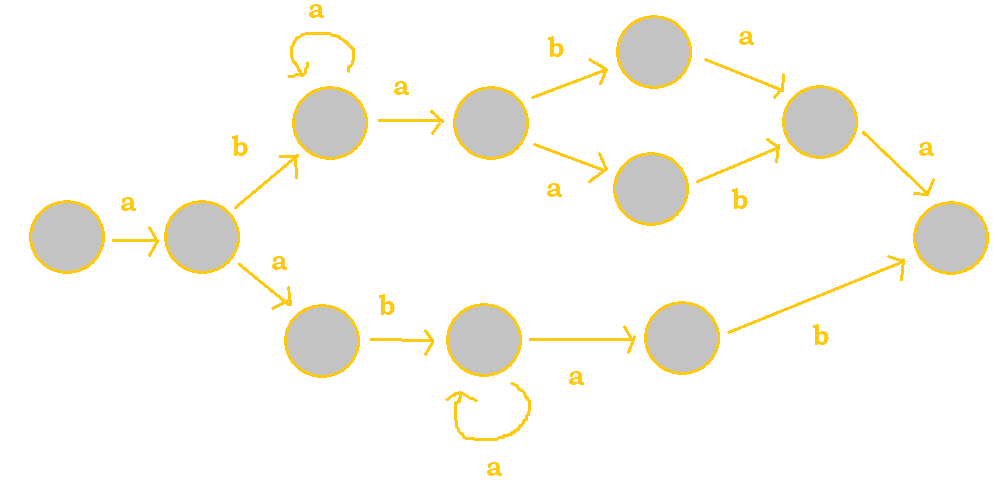

4. Which of the given strings would be accepted by the following FSA?

/a(ba*aba|aba)|(aba*b)//a(ba*a(ba|ab)a)|aba*ab//a((ba*a(ba|ab)a)|(aba*ab))//a((ba*aba|aba)|aba*ab)/- None of the above

For this problem, it would be easier to analyze the FSA rather than looking at the strings one by one. In this FSA, there are two unions that we would have to keep in mind.

Regardless of what "path" is taken, a would always start the string. Now, we have a union; we

can analyze the two subpaths separately. The upper path would produce either /ba*abaa/ or

/ba*aaba/; we can write this as /ba*a(ab|ba)a/.

The lower path would produce /aba*ab/.

Now, we can put these together to get our overall regex of /a((ba*a(ab|ba)a)|(aba*ab))/.

Note that many parentheses were used to clarify what the different union alternatives are. This

regex matches what is written for #3; hence, #3 is our answer.

Authors: Kelly Hong, Raymond Zhao