Computer Number Systems

Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Binary, Octal, Decimal, and Hexadecimal

- Converting between Bases

- Arithmetic for Numbers in Other Bases

- Sample Problems

Introduction

Whenever we work with numbers, we use the decimal base. However, computers use bits, or binary digits, to store numbers and other information. Since binary numbers can get quite lengthy, the octal and hexadecimal (or just hex) bases are also used.

This category does not cover how to represent negative numbers or floats in binary. Occasionally, fractions in other bases may be involved.

Understanding Binary, Octal, Decimal, and Hexadecimal

Just as a summary, binary is base 2, octal is base 8, decimal is base 10, and hex is base 16.

All of these bases have a range that their digits work in. For example, for decimal

base numbers, the digits range from 0 to 9; having a digit of 10 would not make

much sense.

Binary digits have a range of [0, 1], octal with a range of [0, 7], decimal with

[0, 9], and hex with [0, F]. Notice that for hex, a letter is the upper bound. This

is because to represent the numbers 10 to 15, we use letters instead of the actual

number; so for example, 10 is denoted as A, 11 is denoted as B, and so on.

With these ranges, notice that the upper bound is one less than the base; so, with binary,

which is base 2, the upper bound is $2 - 1 = 1$. Also notice that all of them have a

lower bound of 0.

Moving on, a group of 3 bits make up a single octal digit; this is because $111_2 =

((1*2^2)+(1*2^1)+(1*2^0))_{10} = (4 + 2 + 1)_{10} = 7_{10}$, which is the upper bound for the

octal base. Similarly, a group of 4 bits make up a single hex digit; this is because

$1111_2 = ((1*2^3)+(1*2^2)+(1*2^1)+(1*2^0))_{10} = (8 + 4 + 2 + 1)_{10} = 15_{10}$, which

is the upper bound for the hex base.

How bases essentially work is like this:

Say we have the number $167_{10}$. We refer to 7 as the ones digits, 6 as the tens

digit, and 1 as the hundreds digit. In fact, $167_{10}$ can be written as

$((1*100)+(6*10)+(7*1))_{10}$, or $((1*10^2)+(6*10^1)+(7*10^0))_{10}$.

A similar idea applies to other bases. Let's say we have $01101_2$. However,

instead of multiplying each digit by 10 to a certain power, we would multiply it by

2 to a certain power since that's the base we're working with instead. So, $01101_2$

is technically $(0*2^4)+(1*2^3)+(1*2^2)+(0*2^1)+(1*2^0) = 0+8+4+0+1 = 13_{10}$. Of course, just like in base $10$, the leading $0$ in $01101_2$ could have been removed to become $1101_2$. Note that while this evaluation used powers of 2, the overall

calculation was in base 10.

For best success in this category, it would be wise to know the following things:

- The decimal value of each hex digit A, B, C, D, E, F

- The binary value of each hex digit A, B, C, D, E, F

- Powers of 2, up to 4096 (

$2^{16}$) - Powers of 8, up to 4096 (

$8^4$) - Powers of 16, up to 65,536 (

$16^4$)

Converting between Bases

Converting from one base to another is very common and particularly important in representing long binary numbers as shorter octal or hex numbers. Decimal will also be referenced since it is the most common and easiest base for people to understand.

Working with Base 10

The easiest conversion is converting a number in a different base to base 10. In the

previous section, we covered how $01101_2$ is $((0*2^4)+(1*2^3)+(1*2^2)+(0*2^1)+

(1*2^0))_{10} = (0+8+4+0+1)_{10} = 13_{10}$. We will use this tactic to convert any

number to base 10. Here are step-by-step instructions:

- Look at what base you are currently in.

- Starting with the rightmost digit, multiply that digit by

$(base)^0$. - Move left one digit (if there is another digit) and multiply that digit by

$(base)^1$. - Work in a similar pattern to Step 3. However,

$(base)^1$should "increment" to$(base)^2$, then$(base)^3$, etc. - Add up all of the products to get your desired decimal number.

To convert from base 10 to a different base, there is a different process involved. I will convert

the number $12_{10}$ to binary as an example.

First off, I will consider what the biggest power of 2 that can fit into 12 would be. $2^3$

is 8, which fits. $2^4$ is 16, which is too big; so, we will stick with $2^3$. I will

then draw a few slots, which I will later fill in:

Number: ___ ___ ___ ___

These slots go as follows: $2^3$, $2^2$, $2^1$, and $2^0$.

Now, to fill these slots in, I will consider how many times $2^3$ fits into 12: 1. So, I will

fill that slot with a 1.

Number: 1 ___ ___ ___

I will then subtract $1 * 2^3$ from 12 to get 4. Now, I will repeat the process with

the remaining slots. $2^2$ fits into 4 one time, so that slot will be filled in with a 1.

$1 * 2^2$ will be subtracted from 4 to get us 0. $2^1$ and $2^0$ both fit into 0

$0$ times, so those slots are filled in with $0$. Hence our final answer is $1100_2$.

While converting to base 2 only leaves two options for each slot ($0$ or $1$), the process is very similar to converting from base 10 to base 8 and 16 (and any other base for that matter). You find the highest power of the base less than the base 10 number, subtract it as many times as possible, fill in that corresponding slot, and repeat.

Special Conversions with Binary

Now, when it comes to converting among binary, octal, and hex, there are 2 handy tricks to think about. Remember the fact that 3 bits represent an octal digit, and 4 bits represent a hex digit.

To convert from binary to octal, make groups of 3 from right to left; if there are not enough bits, then just add zeros on the left. Afterwards, evaluate each of those 3-bit groups in base 10. These new numbers will be the digits of your octal number.

Let's use an example, $1111011_2$, to prove this. So, we would make the groups 001, 111,

and 011 first. These would evaluate to 1, 7, and 3. So, our octal number is $173_8$.

If we were to do the reverse, then we would write the 3-bit code for each individual digit in

the octal number and remove any leading zeros. So, $173_8$ would get us $001{|}111{|}011$, which

would be reduced to $1111011_2$.

The same idea applies for if you want to convert from binary to hex and vice versa, except that you work with groups of 4 bits instead of 3. Also, you will have to work with the letters A-E, which again, represent 10-15.

When converting between hex and octal or vice versa, you can use this trick to go to binary first and then to the desired base. This trick is very helpful as the numbers you deal with are much smaller, leave you much less prone to computing errors, and could save you a lot of time.

Fractions

These are not frequently tested, but we will cover them here just in case.

To convert a fraction to base 10, it is relatively easy. When we look at decimal numbers like

256.3, we would describe the 3 as the tenths place. This can also be conveyed as

$3*10^{-1}$. We will use this knowledge in our conversions.

First off, you will want to convert the fraction into a decimal for better viewing. With normal

converting, the ones digit would be multiplied by $(base)^0$. Then, the first decimal digit

would be multiplied by $(base)^{-1}$, the second would be multiplied by $(base)^{-2}$, etc.

So, let's say we have $10.11_2$. We would convert this with the following calculation:

$(1*2^1)+(0*2^0)+(1*2^{-1})+(1*2^{-2}) = 2 + 1/2 + 1/4 = 2.75_{10}$.

If we wanted to convert a fraction from base 10 to a different base, the process is a bit more

complicated. Let's convert 7/8 to base 2 as an example.

First off, let's convert this into a decimal once again; we would get 0.875. Then, we will

multiply this number by 2 (to be more general, the base that we want to convert to); we would get

1.75. However, instead of writing down 1.75, we will want to write down the result of

$1.75$ % $2$ (again, you would replace the 2 with whatever base you're converting to),

which is still 1.75 (in this case). We will now multiply this number by 2 again

to get 3.5. We will want to write down $3.5$ % $2$, which is 1.5. This process continues

until we get a remainder of 0.

For this sample problem, here's a summary of the steps we took:

$(0.875*2) \; \% \; 2 = 1.75$$(1.75*2) \; \% \; 2 = 1.5$$(1.5*2) \; \% \; 2 = 1.0$$(1.0*2) \; \% \; 2 = 0$

Our last step would be to look at the results of each step except for the last step. Look

at the first digit in particular; we have 3 1's. So, $0.875_{10} = 0.111_2$.

If we were to generalize this entire process, we would have the following instructions:

- Convert the fraction into a decimal.

- Multiply this decimal by the base you want to convert to.

- Write down the result of

number % targetBase. - Repeat Steps 2-3 until

number % targetBase = 0. - Write down the first digits of the results from each multiplication step (except the last one). This will make up your new converted number.

In the case that you have a mixed fraction, such as 19 4/5, you would want to convert the whole

and fraction part separately. Then, add together their results to get your final converted number.

Arithmetic for Numbers in Other Bases

Arithmetic in other bases is similar to what we would do with numbers in the decimal base. However, we have to keep in mind the different ranges that different bases work in. Also, arithmetic should be done between numbers in the same base; if they are not, then be sure to make any needed base conversions before doing the arithmetic.

Do note that ACSL will only cover division for binary base numbers; however, on this page, we will describe how to do all of the operations, even division, with any base regardless.

Addition

Addition would go as follows:

- Add together the digits.

- Check if this resultant number is within the base's range of valid numbers. If it is out of the range, then divide the number by the base. The quotient will be carried on whereas the remainder becomes the new digit.

- Continue Steps 1-2 until you have finished adding together both numbers entirely.

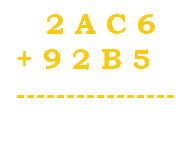

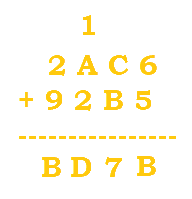

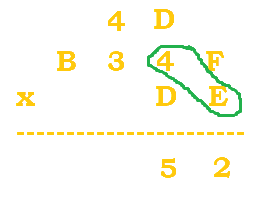

Here's an example (this will be in base 16):

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

This is just the start of our problem. No arithmetic yet. |

|

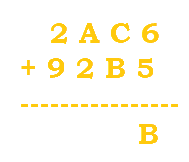

$6+5=11$, or B. Since B is within the range of [0, F], B will be written at the bottom with no numbers to carry. |

|

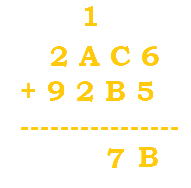

$C+B=12+11=23$. 23 is beyond our range, so we would divide it by 16 to get 1 R7. The 1 is carried while the 7 becomes the new digit. |

|

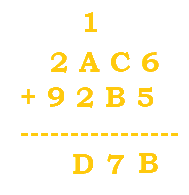

$1+A+2 = 13$, or D. We do not go out of the range, so we just write D at the bottom. |

|

$2+9=11$, or B. We are within the range, so B is simply written at the bottom. |

Subtraction

Subtraction is very similar to decimal subtraction. However, when you need to borrow from the next digit, you would add the base number and not 10. The next digit would still decrement by 1 though.

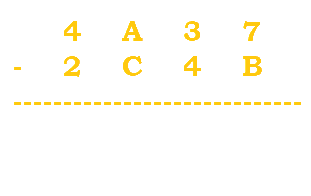

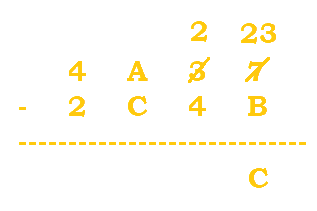

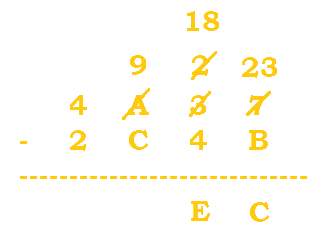

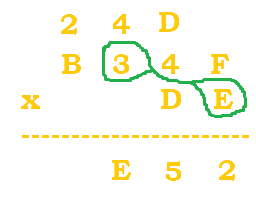

Here's an example (this will also be in base 16):

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

This is just the start of our problem. No arithmetic yet. |

|

$7-B$ would get us a negative number, so we need to borrow. 3 becomes a 2, and 7 becomes $7+16=23$. $23-B=23-11=12=C$. |

|

$2-4$ would get us a negative number, so we need to borrow. A becomes a 9, and 2 becomes $2+16=18$. $18-4=14=E$. |

|

We will need to borrow because $9-C$ is not valid. The 4 becomes a 3, and the 9 becomes $9+16=25$. $25-C=25-12=13=D$. |

|

$3-2=1$. No borrowing is needed. |

Multiplication

Multiplication is done in a similar manner to addition. First, you multiply as normal. If the product is outside of the base's range, then divide the number by the base. The quotient is carried while the remainder becomes the new digit.

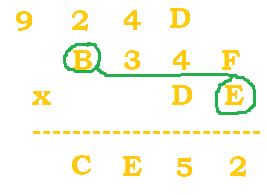

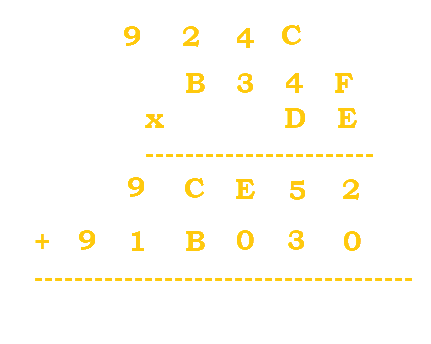

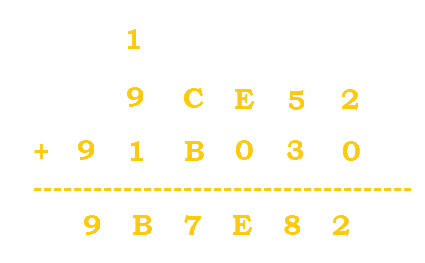

Here's an example (again, this will be in base 16):

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

This is the start of our operation. |

|

$F*E=15*14=210$. $210/16=13 \; R \, 2$. The 13, or D, is carried. The 2 is put at the bottom. |

|

$(4*E)+D=(4*14)+13=69$. $69/16=4 \; R \, 5$. The 4 is carried, and the 5 is put at the bottom. |

|

$(3*E)+4=(3*14)+4=46$. $46/16=2 \; R \, 14$ (or E for 14). |

|

$(B*E)+2=(11*14)+2=156$. $156/16=9 \; R \, 12$ (or C for 12). |

|

There are no calculations to do for the extra carried 9, so it is automatically moved to the bottom. |

|

We now continue to do multiplication with the second digit of DE. A zero is automatically placed first just like in normal multiplication. Then, $D*F=13*15=195$. $195/16=12 \; R \, 3$. C is used in place of 12. |

|

$(D*4)+C=(13*4)+12=64$. $64/16=4 \; R \, 0$. |

|

$(D*3)+4=(13*3)+4=43$. $56/16=2 \; R \, 11$. B replaces 11. |

|

$(B*D)+2=(11*13)+2=145$. $145/16=9 \; R \, 1$. |

|

There are no calculations to do for the extra carried 9, so it is automatically moved to the bottom. |

|

The results are finally added together to get 9B7E82. |

Division

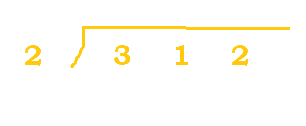

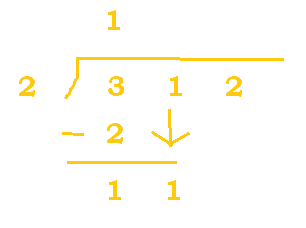

With division, the process of finding how many times the divisor (what you're dividing by) fits into the dividend (what you're dividing) has an extra step to it.

I will jump right into an example, as it is easier to demonstrate while explaining for division in particular. We will

do the operation, $312_4 / 2_4$. First off, we must remember what range of numbers we can work with: [0, 3] (because we're in base 4).

What would also be useful is to list out the results of $2_4 \bullet 1_4$, $2_4 \bullet 2_4$, and $2_4 \bullet 3_4$

(which are $2_4$, $10_4$, and $12_4$ respectively).

Now, we can start. Refer to the table below.

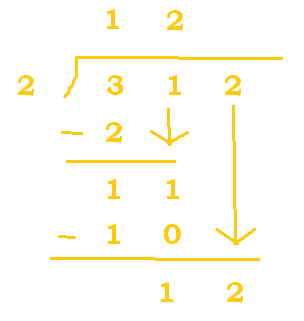

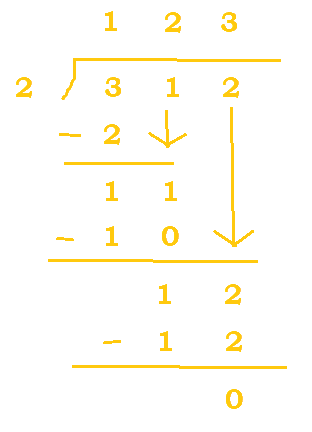

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

This is the start of our problem. |

|

$2_4$ belongs in $3_4$ one time. 1 is put at the top, we do the needed subtraction, and 1 is carried down. We are now left with 11 at the bottom. |

|

$2_4$ belongs in $11_4$ two times since $2_4 * 2_4 = 10_4$. 10 is subtracted from 11 to get 1, and the 2 is carried down. |

|

$2_4$ belongs in $12_4$ three times. 3 is put at the top, 12 is subtracted from 12 (since $2_4 * 3_4 = 12$), and we are left with a remainder of 0. |

If division is still a bit tricky for you, no worries! ACSL mainly focuses on addition/subtraction and sometimes multiplication, so you should be safe.

Sample Problems

1. Convert the hex base number, FA6643, to an octal base number.

Here, we can use the handy special binary conversions. So, we can first convert the hex base number into binary.

$FA6643_{16}$ = $1111 \; 1010 \; 0110 \; 0110 \; 0100 \; 0011$ = $111110100110011001000011_2$.

Now we can make new groups of three from right to left and then re-evaluate the binary number into octal.

$111110100110011001000011$ becomes $111 \; 110 \; 100 \; 110 \; 011 \; 001 \; 000 \; 011$, which evaluates to $76463103$.

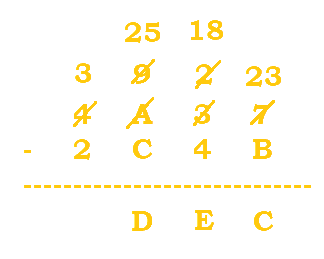

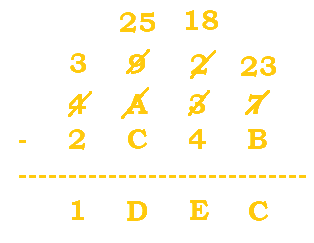

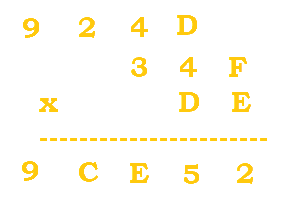

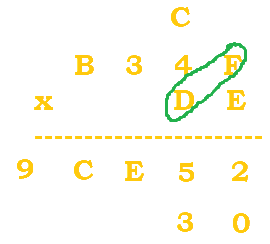

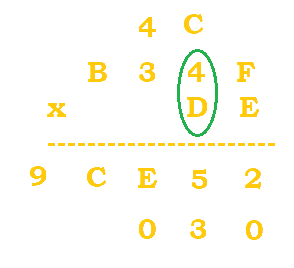

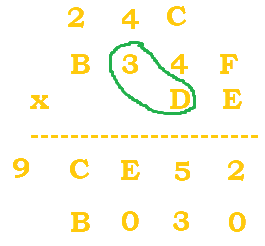

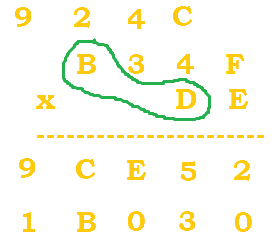

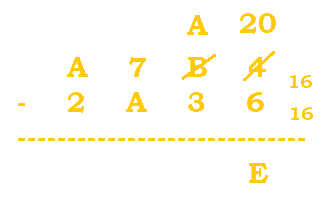

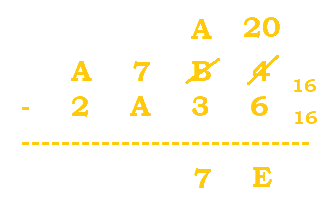

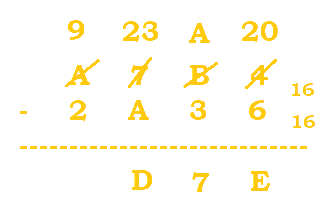

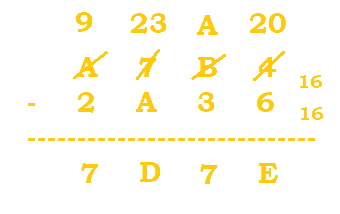

2. Evaluate the following expression: $A7B4_{16} - 2A36_{16}$.

Follow the table below:

| Steps | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

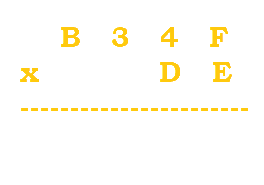

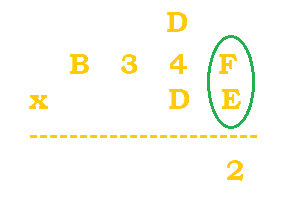

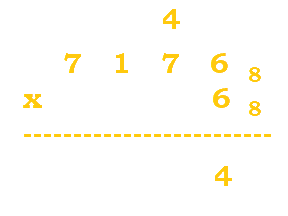

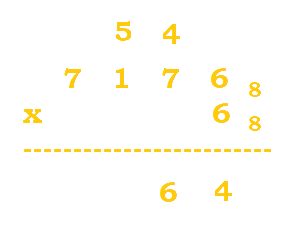

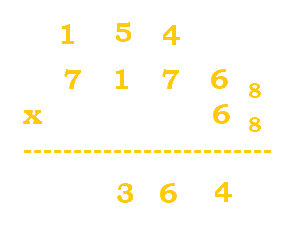

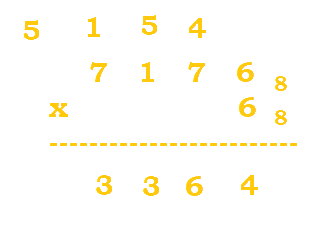

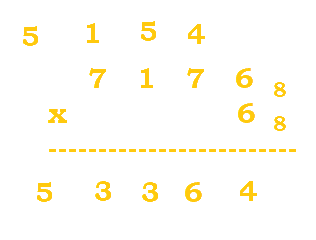

3. Evaluate the following expression: $7176_8 * 6_8$.

Follow the table below:

| Steps | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Solve for x in the following equation: $275_x=360_7$.

Now this problem is pretty cool. Before, we noted that $01101_2$ is $((0*2^4)+(1*2^3)+(1*2^2)+(0*2^1)+(1*2^0))_{10} = (0+8+4+0+1)_{10} = 13_{10}$.

We will use this concept to our advantage.

$275_x=360_7$$2x^2 \; + \; 7x \; + \; 5 \; = \; 360_7$$2x^2 \; + \; 7x \; + \; 5 \; = \; 189_{10}$$2x^2 \; + \; 7x \; - \; 184 \; = \; 0$$(2x+23)(x-8)=0$$x=-23/2 \; , \; 8$

We won't delve into negative bases, so you can just stick with 8 as your final answer.

Author: Kelly Hong, Haroldas Diska (Edits)